Senpai who have lived in Japan long time: “If You Need Help, Go to Antony”

Table of contents

Antony came to Japan when he was 12 years old and graduated from junior high school through university in Japan. He is currently working at the employment counseling service of the Shizuoka Job Station and also works for his own company, Grace, which a wide range of services including translation and interpretation, Japanese language classes, consultation services, insurance, and even candy sales!

Profile

| February 2008 | Arrived in Japan |

| July 2008 | Entered Arai Junior High School in Kosai City |

| January 2009 | Moved to Hamamatsu and transferred to Sanarudai Junior High School in Hamamatsu City |

| April 2012 | Graduated from junior high school. Passed high school entrance exam and entered Kosai High School. |

| May 2014-. September 2014 | Later left Kosai High School and transferred to Ohiradai High School (regular course). |

| Apr 2015 | Graduated from high school and entered Tokiwa University (majoring in global communication) |

| August 2018 | Job search (participated in internship during junior year) |

| March 2019 | Went to Peru on a graduation trip (March). Declined job offer after returning to Japan |

| April 2019 | Did freelance interpreting, translating, and clerical work for remodeling companies, etc. |

| Around June 2019 | Applied for permanent residence as a family and obtained permanent residency. |

| July 2019 | Started working as a part-time employee at the Shizuoka Job Station. |

| April 2020 | Continued to work at the Shizuoka Job Station as Tokaido Sigma became the employer |

| From May 2022 | Start his own company, Grace |

How did you learn Japanese?

Most of the students at Nii Junior High School, where I went to immediately after arriving in Japan, were Japanese, with only three foreign nationals including myself. Of the three, one was born and raised in Japan and spoke Japanese. The other was fluent in both Japanese and foreign languages. Therefore, I was the only foreign student who did not understand Japanese.

I learned Japanese for the first time after coming to Japan. What I kept in mind was (1) to use Japanese as much as possible in my daily life and (2) to speak as if my native language were Japanese. It was OK to make mistakes, so I just tried to speak in Japanese a lot. While asking the kids around me to correct my Japanese, I learned Japanese through daily conversation. Therefore, I did not have to study Japanese or attend Japanese language classes after school in junior high school.

There were so many foreign students at Sanarudai Junior High School that it was commonplace to have them. For that reason, there was a class for foreign students to study Japanese in a separate room. Therefore, I studied Japanese “at a desk” for the first time. For about a year after arriving in Japan, I learned Japanese through daily conversation, but since I did not study in a classroom setting before, I could not read and write kanji very well. After entering Sanarudai Junior High School and starting to study Japanese (at a desk), I think my Japanese language ability per se has improved.

Your first job after graduating from college was at Shizuoka Job Station – what made you choose that job?

Right before working at Job Station, I went to Peru in March for my university graduation trip. I stayed there for about a month, during which I felt that I was heading to a somewhat “boxed-in” life (in terms of going to the company to which I had received an offer). Going into a company, working hard, getting paid, and working as an employee for the rest of your life is a way of life, one which I think is right. However, I felt that this was not the future I was looking for. It was not what I was looking for. That’s why, after returning from my graduation trip, I turned down the job offer. I did not work from April of that year. To this day, I still think that was a drastic decision even for me (laughs).

After graduating from college, I worked as a freelance interpreter, translator, and office worker for about two months (Antoni has worked for a construction company and a remodeling company while he was in school). That was how I was able to make ends meet. In May, I applied for a job posted by Shizuoka Job Station and was hired. When I first saw the job opening, it was an interpreter and representative position (mainly job search support/consultation) at the foreigner consultation service at an employment consultation agency in Shizuoka Prefecture, and I was very attracted to such a job where I could be paid to support foreigners directly. I thought to myself, “Ah yes, this is what I want to do.”

My job at Job Station was a limited-term post until March 2020. Then, at the end of my contract with the prefecture, a company called Tokaido Sigma, which was commissioned by the prefecture to provide consultation services for foreign residents at Job Station, asked, “Why don’t you come work for us?” I decided to go with them because the work I had been doing, and still want to do, as a foreign resident consultation service manager would remain the same, with the only exception that my employer would change from the prefectural government to Tokaido Sigma. Looking back now, I realize that this decision was a major catalyst for my current business.

When I was in charge of the consultation service on the Shizuoka Prefecture contract, I was limited in what I could do because they were a government agency. Of course, although I was still allowed to do a lot of things (e.g., post translations of laws regarding employment for foreigners on Facebook, conduct seminars on employment, etc.) despite the limitations, it was not always easy to do some of the things I wanted to do. After moving on to Tokaido Sigma, I discussed various project ideas with my supervisor, who would say, “Sure, why not? Let’s try it,” “Interesting,” and “This is good,” allowing me to do various things. For example, I have conducted seminars at various locations in Shizuoka Prefecture (universities, technical schools, vocational training schools, Japanese language classes, etc.) and actively used social media. My degree of freedom increased, and in proportion to that, the number of things I could do increased rapidly.

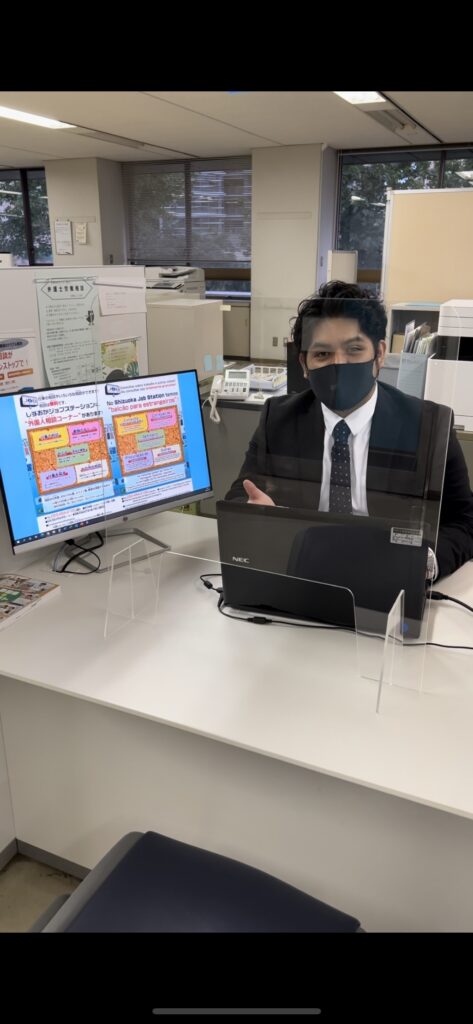

At Shizuoka Job Station / Photo: courtesy of Atony

At Shizuoka Job Station / Photo: courtesy of AtonyWhat kind of work do you currently do?

I work as an interpreter and am in charge of the foreigner consultation service (job hunting support) at Shizuoka Job Station from Monday to Friday from 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. and work at Grace otherwise. At Grace, we work on translation/interpretation, consultation, and Japanese language classes. When I was in university, I took a Japanese language teacher training course, from which I got the certification to offer online Japanese language classes. In 2022, I held a six-month class called “Japanese for Caregivers.” Our other businesses include consultation and insurance, and I recently even created a confectionery shop called Grace Dulce Sabor.

Alfajores(South American sweets) sold at Grace Dulce Sabol / Photo: JP-MIRAI Portal

Alfajores(South American sweets) sold at Grace Dulce Sabol / Photo: JP-MIRAI PortalWhat made you get into the insurance business?

When I started my own company, one of my main goals was to create a “one-stop service” where people would say “go to Antoni” if they need help. We started out as a one-stop service for foreigners, and I was thinking of creating a contact point that could be used by various people regardless of nationality or status of residence, which eventually led me to the insurance business.

Sadly, there are many cases of foreign residents who have not been insured/ did not know the extent to which their insurance would cover them, and thus end up with a heavy financial burden in the event of an accident or other incident. It is also true that there are situations where it is not easy to save and invest for the future. I came to the conclusion that the insurance business is essential for them to be able to live with peace of mind and to make real progress in settling down.

There is a word in Japanese called kyosei (“coexistence”), but I personally do not like it very much. I understand that coexistence means “different individuals living together,” but the word always carries with it the image of “together but always different.” This is true even if coexistence has been successfully developed. I have always wished for a society where diversity is a matter of course. I think that there is no need to go to the trouble of separating Japanese and foreigners and organizing them so that they “coexist.” I think it’s better to say, “Because they’re young.” When I thought about what kind of support I can provide when foreigners get into an accident or are in trouble, I realized that the insurance business is essential to realizing such a society.

When I started in the business, I learned about insurance from the CEO of an insurance agency in Shizuoka, with whom I had a connection before, and the CEO of an insurance company in Kanagawa. I also obtained certification and now sell insurance mainly to foreigners. While selling insurance is one of my objectives, I want them, above all, to consult with me. I listen to what kind of problems they have, what they are worried about, what their budget is, etc., and then I tell them what kind of insurance I can offer.

What challenges do you think need to be overcome for foreigners to be active in society?

In the consultation service at Shizuoka Job Station, the number of consultations from foreign students is very much increasing. When it comes to consultations from foreigners, most of them, excluding students, are from foreign residents in their 30s to 50s. We receive a variety of consultations from each of our clients. One of the common traits that I find is “Japanese proficiency.” My experience is that although I am not Japanese-like, when I speak Japanese and use both Japanese and my native culture in socializing with others, I tend to give off the impression (to Japanese people) that I’m easy to talk to and that they start to listen to what I have to say. In Japan, the line between the “in-group” and “out-group” is very clear, so I think it is very important to go “in”, and The way to cut “in” is to eat (Japanese) food (e.g., Japanese food with people at work, etc.) and to be “polite.” When you learn Japanese, you are also able to pick up Japanese culture. If you can understand Japanese culture, I think you’ll be able to overcome some hurdles in living and working in Japan. It doesn’t have to be perfect Japanese, but just being able to have a basic-level conversation and communicate with others will make a big difference.

What do you think local residents, local governments, and other stakeholders in our community should do to help young Hispanic people from South America who come to Japan with dreams to live their own lives and be more active in Japanese society?

In my opinion, whether the support is sufficient or not depends on how you look at it. If it is, we think they’re being spoiled. On the other hand, if it is not, I think that is not good either. Nowadays, different people and organizations are providing various support for foreigners. Among them, if I dare say so, it is for “promoting foreigner participation.” Currently, I think that even if an event is held, only foreigners who are interested would participate. Some people would not even know about the event in the first place. I would like to ask the local government and support groups to devise ways to encourage more foreigners to participate in local activities. However, there is a dilemma. I personally believe that in order for foreigners themselves to become active in society, there is no point unless they make the first move. If the number of foreigners active in society increases, the people around them will become interested in participating in local events, and more foreigners will join them. I hope that connections could be formed this way.

Do you have any messages of support or advice for young people who want to come to Japan or for children and youth with foreign roots, including Hispanics from South America, living in Japan?

Study and work are tools, not objectives. Therefore, I would like children and young people who will enter society in the future to choose “good tools.”

I think they should choose the tools that are easiest for them to use and move forward so that they can reach and accomplish the things and goals that they want with “dreams I want to achieve” or “challenges I want to take on” in the future. Frankly speaking, I don’t think kids aged 14 or 15 will have a concrete image of what I am talking about when I tell them this. In that sense, it is difficult for them to decide their future in Japan before they graduate from high school or enter society. However, that is just the status quo, and I want them to acquire the tools and weapons that will allow them to make the most of that.

In my case, the tool was university (higher education). My background as a foreigner who speaks Japanese, graduated from a Japanese university, and is now working in a socially responsible job has allowed me to speak out more, connect with various people, and expand the scope of my activities, leading me to where I am today. If I had not turned down that job offer after graduation, I would not be where I am today and would not have all the connections I have today.

Senpai who have lived in Japan long time: From Experience as a Disaster Victim to Community Activism

In this article, we interviewed Ajipe Oshiro Roxana Angelica, a second-generation nikkei from Lima, Peru.